Sunkissed: Reimagining Redistribution of Resources in a Time of Climate Crisis

An essay by Suzanne Dhaliwal on the agency of amplifying voices at the frontline of decolonisation and decarbonisation.

This essay is part of Issue #1 “Agents Provocateurs: agitate normality”, a bimonthly series curated by KoozArch on the agency of architecture and the architect. It is also part of KoozArch's focus dedicated to Biennale Architettura 2023 - 18th International Architecture Exhibition The Laboratory of the Future, curated by Lesley Lokko and organised by La Biennale di Venezia. The International Exhibition is open in Venice from May 20 to November 26.

In response to the complex and multiple crises facing the global climate and community, this year’s Venice Biennale invited me to explore decolonisation and decarbonisation as part of an expanded umbrella of architecture. For the past 15 years, my work has centered on amplifying those on the frontlines of extractivism who are both resisting climate change and feeling its impacts first. As a climate justice campaigner and Executive Director of the U.K. Tar Sands Network, I have worked alongside those on the frontline lines of extractivism in the Canadian Tar Sands, the Niger Delta, the Amazon, also resisting environmental injustice across Europe.

For the past 15 years, my work has centered on amplifying those on the frontlines of extractivism who are both resisting climate change and feeling its impacts first.

This frontline work has taken place in parallel to a paradigm shift that redefines the relationship between mining, extractivism and the climate crisis. Such a paradigm requires deeply listening to those working to resist the violent colonial devastation of key ecosystems, cultures and ways of life across the planet. To develop strategies to work in allyship with frontline Black, Indigenous, and People of Colour communities, it has been crucial to establish an interdisciplinary practice.

A paradigm shift requires deeply listening to those working to resist the violent colonial devastation of key ecosystems, cultures and ways of life across the planet.

As an agent provocateur working to make these webs of capital and power visible between the U.K. and the globe, it has been crucial to shape shift: to deeply embed oneself into the economic intricacies that connect an insurance provider at the Lloyds building in London to the beginnings of the exploitation of human energy and life; slavery to the current fossil fuel and the economic system we find ourselves in with our daily lives.

This making visible the invisible through storytelling, this effort of amplifying frontline voices requires an interdisciplinary creative leap to translate it into the strategies that make up the architecture of climate movements. To trace the root cause of the climate crisis in capitalism requires a deep untangling of the economic web that drives resource extractivism yet evades accountability for its human rights and ecological crimes.

Making visible the invisible through storytelling requires an interdisciplinary creative leap.

We now find ourselves in a moment in time where climate campaigns have reached a public awareness unlike anything we have experienced before. The fact that the themes of the Venice Biennale are centered on decolonisation and decarbonisation is a testament to that seismic cultural shift that prioritises a new vision of the world.

We now find ourselves in a moment in time where climate campaigns have reached a public awareness unlike anything we have experienced before. The fact that the themes of the Venice Biennale are centered on decolonisation and decarbonisation is a testament to that seismic cultural shift that prioritises a new vision of the world.

While so much of activism looks to the past—revealing how we got to the current ecological and social crisis due to exploitation of resources, white supremacy and colonial violence—the invitation to inhabit the Laboratory of the Future enabled a new perspective to rethink the questions of climate colonialism, design and creativity. There were the resources to meander with and pay attention to materials and enter into questions that are not often readily available when responding to the immediacy and stresses of ecological and humanitarian disasters that the climate crisis has thrust us into. Rather than being a real world intervention—like shutting down a pipeline, or taking over a fossil fuel company headquarters—the format of the exhibition offered generosity of space, time, materials, capacity for collaboration and a levity I had not experienced since I began working.

"The Laboratory of the Future" brought me back to the philosophical space which first connected me to the gravity of the climate crisis.

The Laboratory of the Future brought me back to the philosophical space which first connected me to the gravity of the climate crisis. It was an interdisciplinary investigation into traditional ecological knowledge, time spent on the land, in community, in embodied investigation which first gave me the insights, data and frameworks to work on imagining a paradigm shift away from colonialism.

What are the creative and design principles that we need to reimagine to respond to the multiple ecological and social crises we are facing today? What is it about the discipline of architecture that gives us the space to reimagine our relationship with the environment and our place in the world at this time?

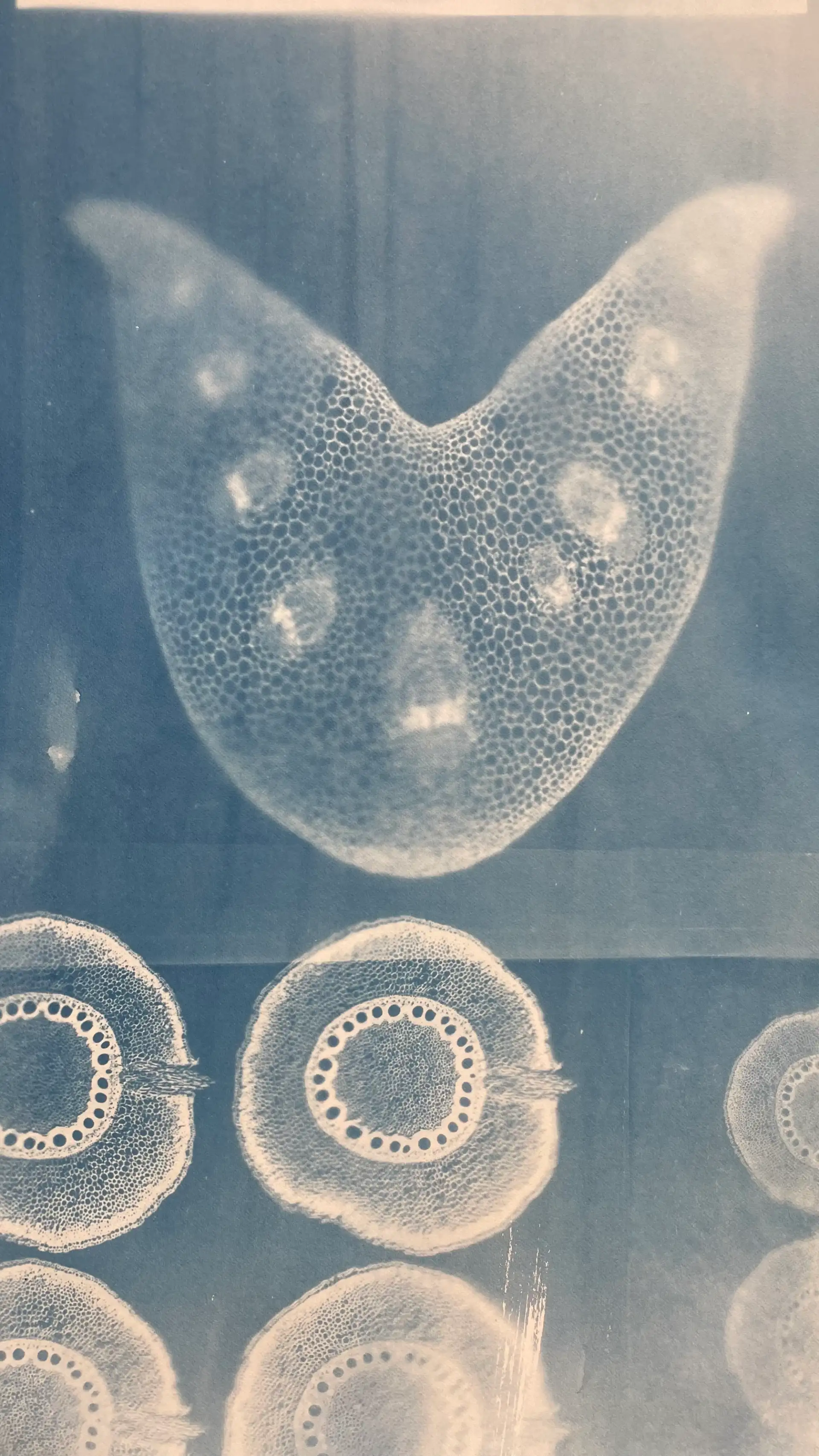

One of the first things I came to think about was the demarcation between inside and outside. The membranes which make up our built environment offer us shelter from the world and also allow us to be in it. They inscribe how we see ourselves situated within and separated from our environment.

What are the creative and design principles that we need to reimagine to respond to the multiple ecological and social crises we are facing today?

The current ecological crisis sees its foundations emerge from a widening separation between ourselves—our cultures and economies—from the natural environment. The over exploitation of resources to fuel our lives has reached unprecedented proportions due to our increasing sense of superiority and lack of daily interaction and immediate interdependence with biodiversity and ecosystems. Therefore, the invitation to participate in a laboratory of the future felt like an investigation into this fundamental spatio-temporal relationship between the inner and outer. What would it look like to rethink this relationship between inside and outside? The semi-permeable membrane became a first point of inspiration.

A semi-permeable membrane is a live serving mechanism, allowing us to redistribute resources throughout our bodies with a subtle and specific negotiation with our environment, always orientated towards life, homeostasis and balance.

The current ecological crisis sees its foundations emerge from a widening separation between ourselves—our cultures and economies—from the natural environment.

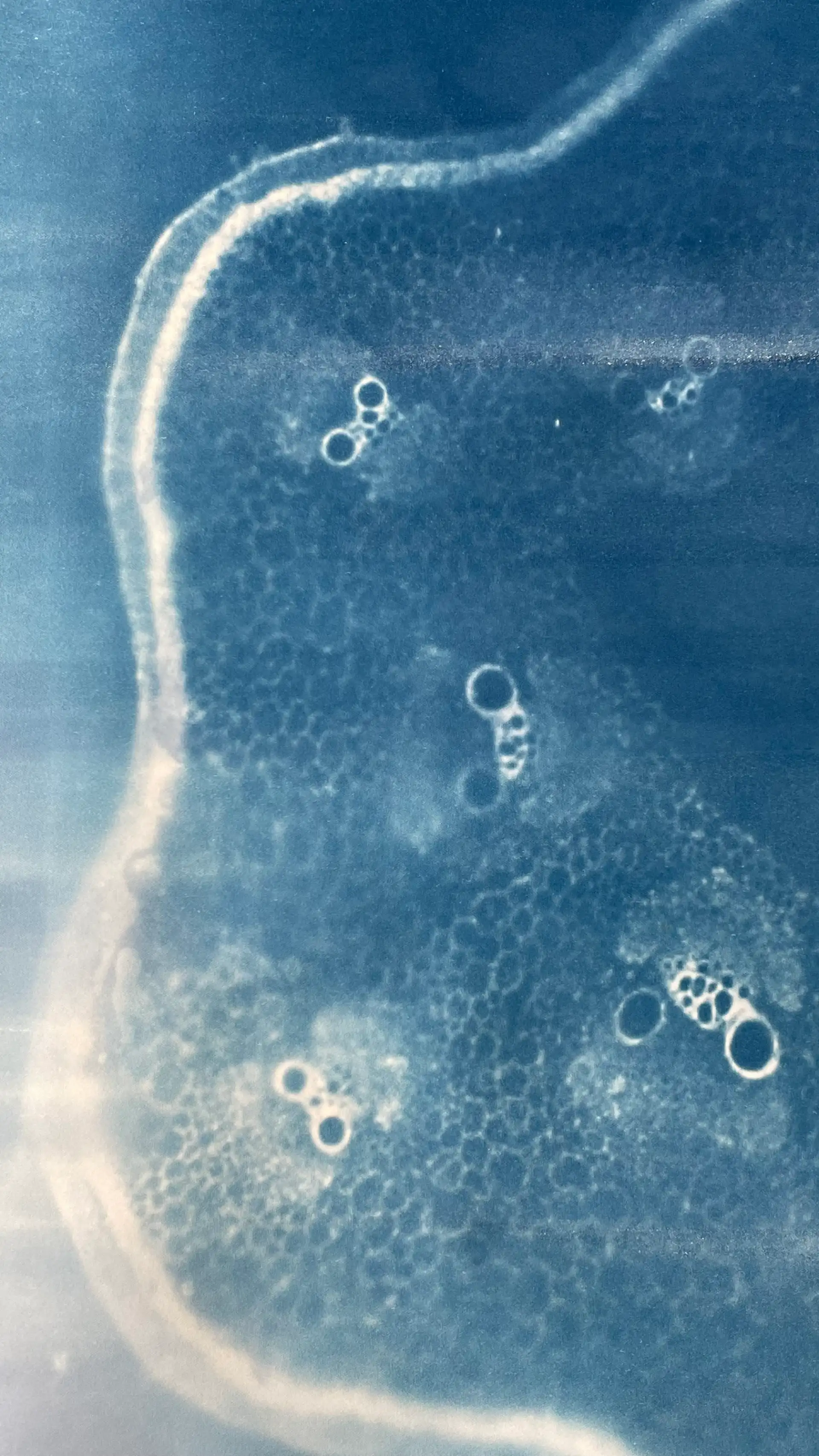

In a series of “sunkissed images”, the semi-permeable membrane begins as a point of inspiration to consider how we relate to differences, barriers and resource distribution from a holistic and life-oriented principle. The semi-permeable membrane can be designed to facilitate life processes such as osmosis, desalination, homeostasis, the protection of organs and distribution of key biochemical agents such as hormones.

At the beginning of the process, I was living on a small island in Croatia and began experimenting with anthotypes. I was working with natural materials, seeing how the dyes worked with fixing images and how they responded to the negatives felt like a possible way to explore this concept further.

However, due to the timeline of the Biennale, a vital ingredient was missing: the sun! How could I still work with this initial impulse? I began to research the possibilities of UV lights and other adaptive technologies which could mimic sunlight. I immediately realised that new design principles will be required as we transition from a carbon-based economy to one centered on regenerative design. There will need to be compromises if the original materials are not fit for purpose even though they are the most “sustainable.” In my own little laboratory, compromises were made to work with cyanotypes. They have more of an ecological impact but also stand the test of time in the Arsenale. Then the question of scale appeared: scaling up the works required bigger pieces. Here were days of frustration with this, however working with architect Jan Lewicki we came up with the idea of making large transparencies in a long roll that would work with the UV lights and also allow to scale up the images.

New design principles will be required as we transition from a carbon-based economy to one centered on regenerative design.

Working with the cyanotypes allowed me to linger into the principles of the semi-permeable membranes in an imaginative and poetic way. Critical resourcefulness—going beyond intellectualising work—is something we will need to do more as we unpack and move towardsdecolonisation and decarbonisation.

My hope is that my work will awaken a conversation about softening the borders in a time of hostile environments, prioritising adaptive technologies that respond to a changing and volatile environment. Art and design strategies should respond to the crisis and be orientated towards life forces. The natural order has been thrown off course, so unprecedented attentiveness to the environment and prolonged investigations into the current ecological and social dynamics need to be fostered—the semipermeable membrane is just one of many ideas that can help envision the needed balance.

Critical resourcefulness—going beyond intellectualising work—is something we will need to do more as we unpack and move towards decolonisation and decarbonisation.

We need to find clarity and collaboration in a time of chaos, to redistribute resources to support those with lived experience of the crisis, to access the space-time to think, create, design and philosophise. This will require working in the dark, the unknown, experimenting with what is at hand, days of imagining and willing into solutions, yearning into scaling up prototypes, failing, being content with the mess along the way and being open to being surprised by unexpected combinations and forms that move the inquiry in novel directions.

We will need to move beyond fixed exhibition spaces to unlock this potential. While the walls should speak for themselves I hope spaces will be convened to continue to tease out the myriad of possibilities we will need in creating the "laboratories of the future."

We will need to move beyond fixed exhibition spaces to unlock this potential.

How will we activate each other? How will we know what our works have initiated, what strategies have emerged from the ideas placed together under the umbrella of architecture at this pivotal time? How will architecture nourish and care for interdisciplinary practices? How are we going to hold accountable for this laboratory of the future?

I still have a lot of questions and one certainty: life is hanging in a delicate balance.

This essay was originally published by KoozArch as part of Issue #1 “Agents Provocateurs: agitate normality”, a bimonthly series on the agency of architecture and the architect.